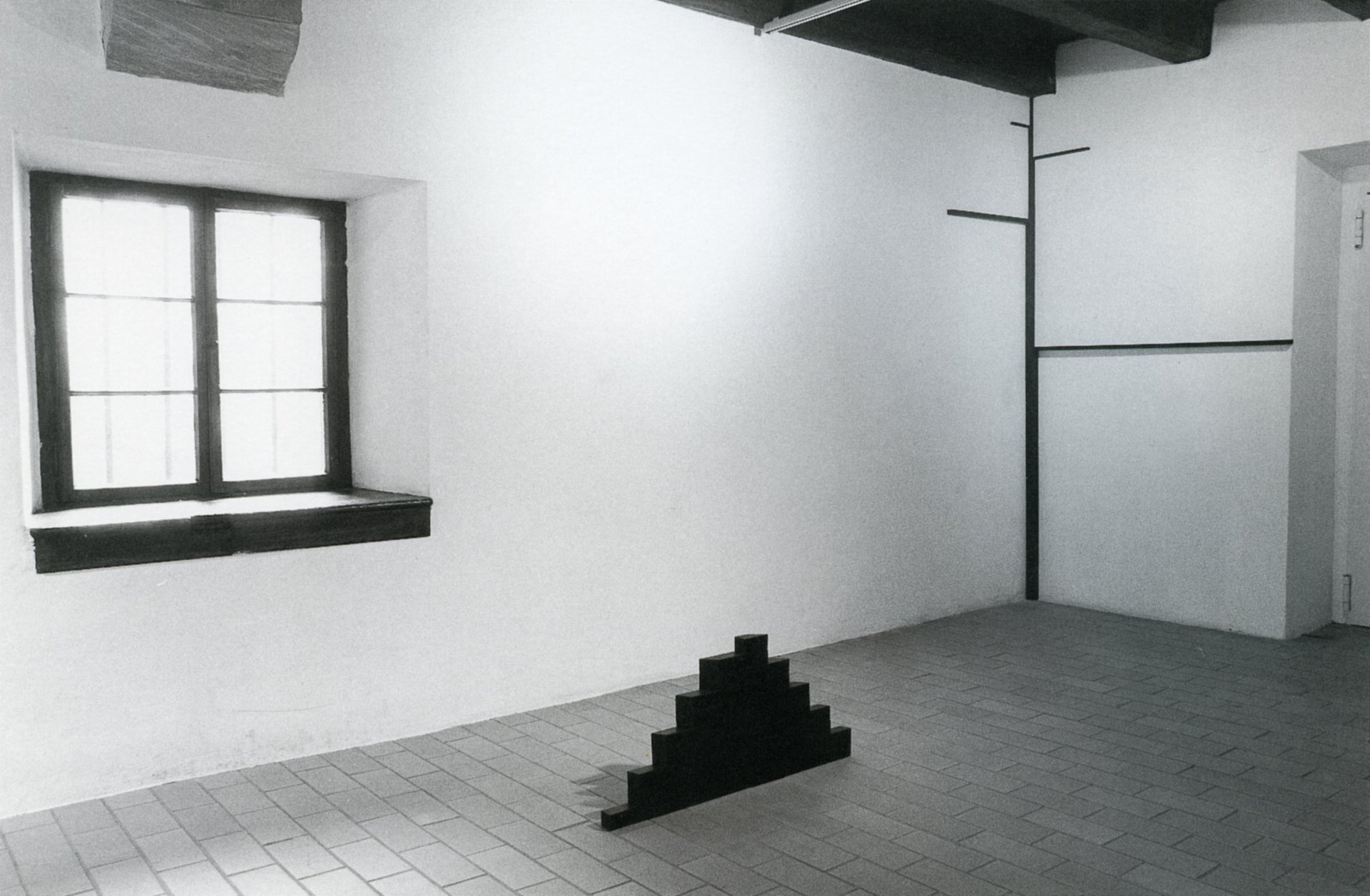

"no", says norman dilworth, he would never imitate nature, never represent it, only work along side it using its principles. so a black rod can behave like a caterpillar, even if that is not intentional. other such rods by dilworth even rise up from the floor and appear to move along the ground in the movement structure of progression apparently naturally. the works suggest a behaviour. other wooden rods, tied together at the end, stand teetering on the floor, thrusting their spines upwards as if they had feet all around, not all of which were used at once, or else they seem to dance oscillating about themselves. dilworth shows me a shell which he keeps in his studio. it has never occurred to him to represent it, but he is stimulated by its structure. "i don't want to find an image in it. it is the parallel to nature which fascinates me. i don't want to work from nature either. i'm working from the opposite direction. i'm objective in what i do," dilworth explains to me. "paradoxically, you get nearer to nature if you eliminate mimicry." he feels he is closer to artists like paul klee and hans arp, who once declared: "we allow the work lo be as nature does".

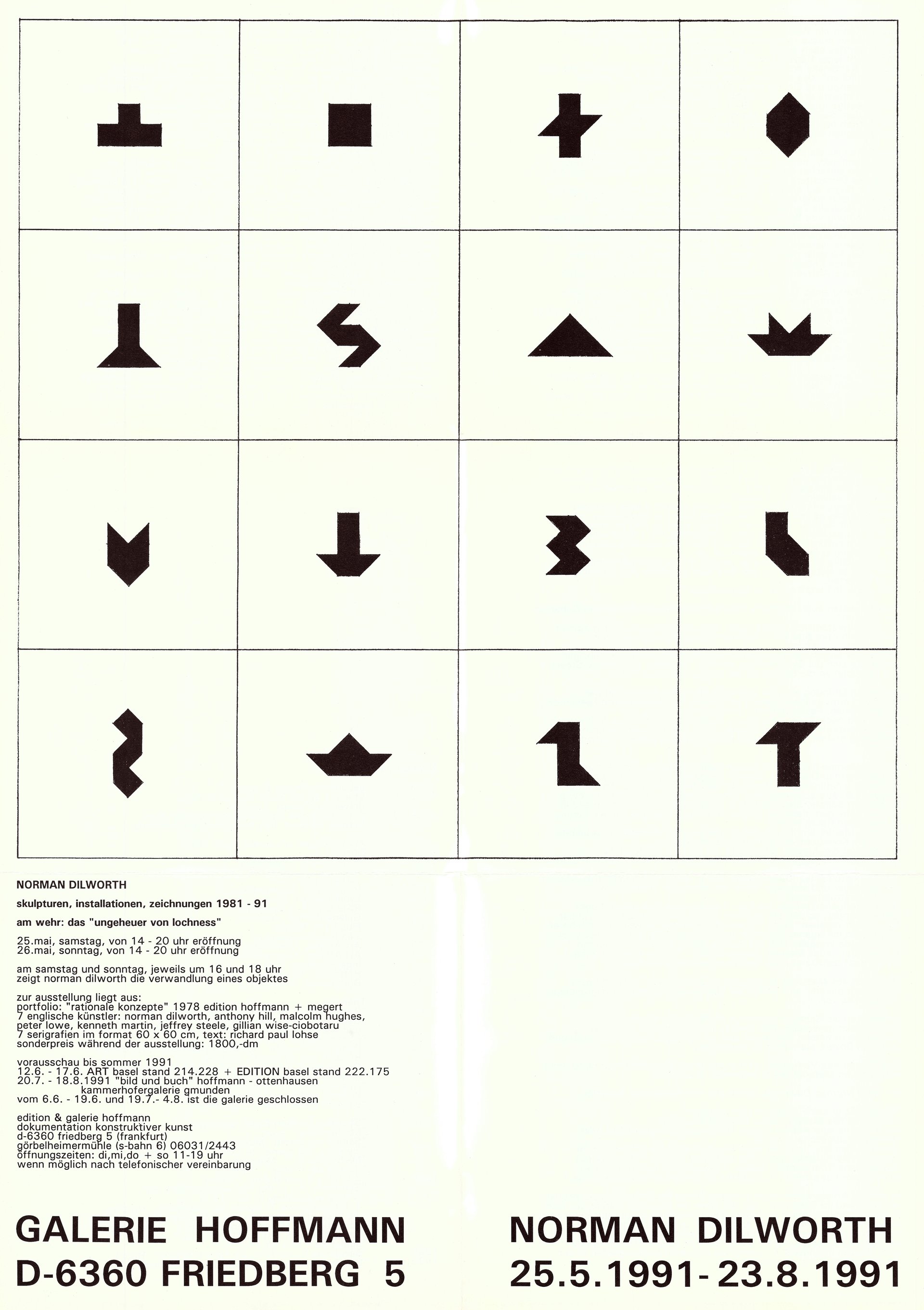

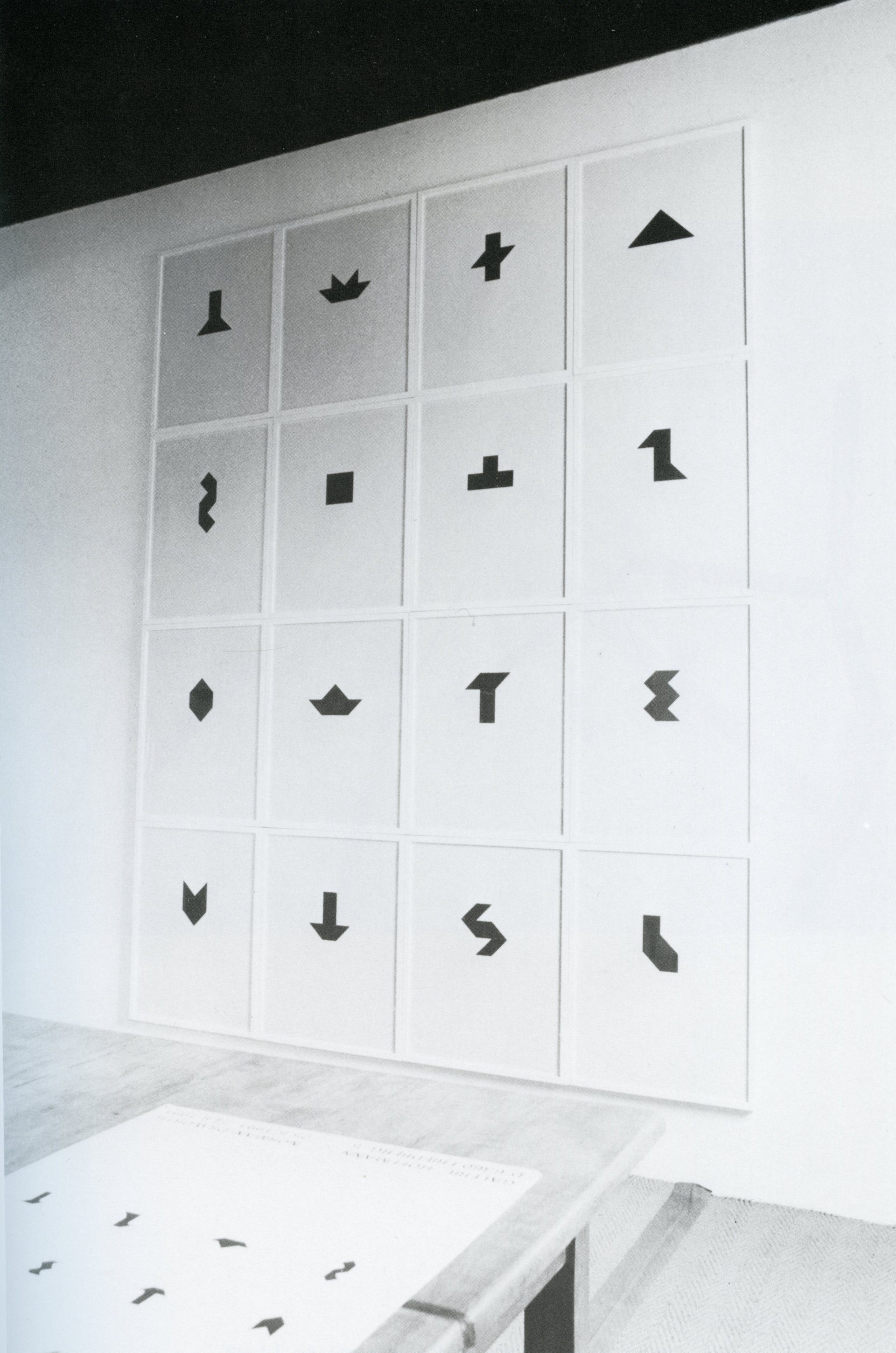

why shouldn't abstract forms call upon gestural associations? but this is by no means obvious. nothing reminiscent of the figurative and the narrative is anathema to orthodox constructivists. the english constructivists of the sixties and seventies, who also called themselves systems artists (anthony hill, jeffrey steele and others), believed in the beauty of mathematical form: they presented order as a spiritual order, movement of serial form, balanced proportions of the elements of an image to each other, progressions, field structures, developments of forms... what was the point of having associations with anthropology or animism–as if constructivist forms could not only stand in a particular relationship, but also show a behaviour of their own?

antje von graevenitz, 1991. excerpt, translation from the original german by sebastian wormell